Calderdale history timeline 1700 - 1800AD : Section 4

Section 1 | Section 2 | Section 3 | Section 4

Producing

cloth to the specifications of a foreign customers sample introduced

Calderdale manufacturers to a route through which they could establish

contact with overseas markets. By shipping cloth direct to the order

of customers abroad they began to develop their own independent trade

networks and ultimately challenged the traditional monopoly of exporting

enjoyed by merchants.

Producing

cloth to the specifications of a foreign customers sample introduced

Calderdale manufacturers to a route through which they could establish

contact with overseas markets. By shipping cloth direct to the order

of customers abroad they began to develop their own independent trade

networks and ultimately challenged the traditional monopoly of exporting

enjoyed by merchants.

"...of late some of the makers in Halifax...parish have sent their goods abroad without the intervention of our merchants".

To assume mercantile activity and compete successfully in distant lands it was vitally important for emergent merchant-manufacturers to establish correspondence with agents residing in foreign ports who could arrange orders, dispose of shipments and also provide accurate knowledge of trading conditions, product preferences and changing tastes.

Merchant-manufacturers developed access to commercial information, which as increasingly large scale producers and exporters, not only guided their decision making in response to rapidly changing demands, but also enabled them to gain control of the link between the making of cloth and its ultimate market.

This ability to innovate and weave different varieties of cloth confirmed the occupational and community distance beginning to open between domestic clothiers and merchant-manufacturers.

Domestic clothiers often had sparse knowledge of the conditions prevailing in export markets and therefore, had little choice but to continue weaving limited amounts of standard kersey for sale and a quick return at the best price they could get at the Piece Hall's weekly market.

Samuel

Hill, who organised his manufacturing from the aptly named Making

Place in Soyland (see image opposite), is a remarkable example of

the age of the merchant-manufacturer. His documents reveal that his

annual income in the 1730s and 1740s was over £30,000; a fortune

by the standards of the day.

Samuel

Hill, who organised his manufacturing from the aptly named Making

Place in Soyland (see image opposite), is a remarkable example of

the age of the merchant-manufacturer. His documents reveal that his

annual income in the 1730s and 1740s was over £30,000; a fortune

by the standards of the day.

From his surviving sample and letter books we can see that Hill had accounts with British, Dutch and other European merchants. He diversified from making kersey's into shalloons and other worsted goods. From his base in Soyland, Hill eventually developed an impressive range of woollen and worsted cloths which he exported widely in Northern Europe, Spain, Portugal and Italy.

Some of his cloth found its way to the markets of St. Petersburg in

Russia and the bazaars of Persia.

Some of his cloth found its way to the markets of St. Petersburg in

Russia and the bazaars of Persia.

To manufacture such a variety and quantity of cloth Hill must have been able to call upon and manage a large workforce numbering many hundreds of cottage based weavers and spinners, and employ the services of skilled craft specialists such as combers, dyers and croppers.

"The woollen manufacture in these parts has greatly flourished. Such as that of the narrow cloth, Bath coatings, shalloons, everlastings a sort of coarse broadcloth with black hair lists for Portugal and with blue for Turkey, Says of a deep colour for Guinea; the last packed in pieces of twelve yard and a half wrapped in an oil cloth painted with Negroes, elephants etc. in order to captivate these poor people; and perhaps one of these bundles and a bottle of rum may be the price of a man in the infamous trade. Many blood red cloths are exported to Italy from whence they are supposed to be sent to Turkey. The blues are sold in Norway." Thomas Pennant, 1774

From the 1730s the emergence of a "culture of commerce", driven by an emerging consumerism in Europe and encouraged by global trading through colonies and by slavery, sustained the demand for large orders of cloth and created work which appeared to benefit everyone involved in cloth making.

This massive increase in production was made possible by the extensive putting-out of work by manufacturers within the arrangements of the domestic system. Regular employment provided economic security and a relatively high standard of living. After all, working for money wages paid by richer clothiers had been accepted custom and practice by many young spinners and weavers for "time out of mind".

With the capability to supply and compete in national and international markets merchant-manufacturers could only survive cut-throat competition by adopting new, more entrepreneurial, attitudes. Unlike domestic clothiers who often worked alongside their journeymen, merchant-manufacturers increasingly became supervisors of workforces and arrangers of production schedules. By adopting aspects of managerial and organisational arrangements prevalent in the contemporary worsted and cotton trades, merchant-manufacturers embarked upon effectively exercising control over all stages and processes of cloth making.

"There is...a very considerable manufactory of kerseys, and half-thicks, also Bockings and baize, principally in the hands of merchants of property in the neighbourhood of Sowerby, and made in the valley from Sowerby Bridge up to Ripponden, and higher. The whole of the British navy is clothed from this source. Large quantities are also, in times of peace, sent to Holland and to America." A Description of the Country from thirty to forty miles around Manchester. John Aiken, 1795.

The

new business practices of large scale production extended managerial

authority and also revealed that merchant-manufacturers held radically

different social and manufacturing motivations compared to those traditionally

respected by either merchants or clothiers. The unmatched wealth and

increasing collective dominance of the merchant-manufacturers over

the industry of the parish eroded the long held equilibrium of production

and ushered in an unaccustomed awareness of social division.

The

new business practices of large scale production extended managerial

authority and also revealed that merchant-manufacturers held radically

different social and manufacturing motivations compared to those traditionally

respected by either merchants or clothiers. The unmatched wealth and

increasing collective dominance of the merchant-manufacturers over

the industry of the parish eroded the long held equilibrium of production

and ushered in an unaccustomed awareness of social division.

"It is evident that merchants concentrating in themselves the whole process of a manufactory, from the raw wool to the finished piece, have an advantage over those who permit the article to pass through a variety of hands, each of which takes a profit" A Description of the Country from thirty to forty miles around Manchester. John Aiken, 1795.

By

organising manufacturing on an industrial scale and imposing firmly

managed production regimes merchant-manufacturers not only escaped

the "weekly round" of the public market but also directly

challenged conventional obligations which had evolved over hundreds

of years and were widely considered to be the "wisdom of ages

past" sustaining social stability and a sense of community.

By

organising manufacturing on an industrial scale and imposing firmly

managed production regimes merchant-manufacturers not only escaped

the "weekly round" of the public market but also directly

challenged conventional obligations which had evolved over hundreds

of years and were widely considered to be the "wisdom of ages

past" sustaining social stability and a sense of community.

A fundamental change occurred, social status and the age old expectation of gaining opportunities for social advancement by moving from journeyman into the ranks of domestic clothier steadily evaporated as large numbers of weavers and their families were reduced to a state of wage dependency from which they could not escape.

A new work culture emerged which stressed the difference between capital and labour, roles that had never been significant in the paternalist clothier and journeyman arrangement of production, and substituted a master and worker relationship dictated by the impersonal conditions of the market economy. For the vast majority the pace of work would be no longer influenced by the rhythm of the household but directed by the obligations and constraints of an employers work schedule.

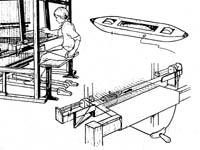

The

fly shuttle loom was in widespread use in the woollen industry by

the 1760s. The adoption of this innovation not only speeded up weaving

and increased productivity it also created a demand for yarn which

domestic spinners using the single spindle great wheel found difficult

to match.

The

fly shuttle loom was in widespread use in the woollen industry by

the 1760s. The adoption of this innovation not only speeded up weaving

and increased productivity it also created a demand for yarn which

domestic spinners using the single spindle great wheel found difficult

to match.

To ensure adequate supplies of yarn manufacturers began to install hand powered scribbling and carding engines, billies and jennies in their workshops and warehouses. Once the yarn had been spun warping mills enabled the making up of a measured warp accurately and quickly.

The

new preparation and spinning machines improved the regularity of the

yarn thereby improving the quality of the cloth.

The

new preparation and spinning machines improved the regularity of the

yarn thereby improving the quality of the cloth.

Cottage weavers employed by merchant-manufacturers would carry their woven cloth to their masters warehouse to receive payment and collect warp and weft for their next piece.

To increase supervision and control over the weaving process manufacturers began to build loomshops adjacent to their workshops and warehouses.

The

transfer to the factory system for worsteds and woollens followed

different routes. Although generalisations are difficult to make,

as there was no such thing as an average concern, certain trends can

be noticed.

The

transfer to the factory system for worsteds and woollens followed

different routes. Although generalisations are difficult to make,

as there was no such thing as an average concern, certain trends can

be noticed.

Like cotton, worsted yarn has a good tensile strength. This feature made worsted suitable for spinning machines adapted from the cotton industry. Worsted spinning mills were similar to those developed by Richard Arkwright (see portrait).

Building a four or five storey water-powered mill and installing machinery was expensive. Worsted masters financed the construction of their mills from the profits they had made by organising the putting-out system and investments from their business contacts.

In

1792 Thomas Edmondson built a worsted spinning mill at Mytholmroyd,

one of the earliest in the county. Operating worsted spinning frames

did not require much experience or skill, the workforce of early worsted

mills consisted mainly of young women and juvenile boys and girls.

In

1792 Thomas Edmondson built a worsted spinning mill at Mytholmroyd,

one of the earliest in the county. Operating worsted spinning frames

did not require much experience or skill, the workforce of early worsted

mills consisted mainly of young women and juvenile boys and girls.

Most of the earliest woollen mills in Calderdale were financed by wealthy merchant-manufacturers or merchants taking up the making of cloth. Woollen mills developed with the mechanisation of the preparatory stages of cloth making.

At first water powered scribbling and carding machines were installed in the merchant-manufacturers fulling mills. Gradually, because of the relatively slow rate of technological innovation in the woollen industry, more processes were incorporated as they became mechanised.

The emergence of mills mark a crucial turning point in the history of woollen cloth production. As each stage of the process was mechanised and centralised in the factory system a progressive transformation of the domestic system and established labour relations took place.

The

topography of Calderdale provided a prime situation for early mill

builders. Advantage was taken of abundant streams to provide power

capable of driving machinery for textile processes when it became

possible to perform them mechanically.

The

topography of Calderdale provided a prime situation for early mill

builders. Advantage was taken of abundant streams to provide power

capable of driving machinery for textile processes when it became

possible to perform them mechanically.

The building of turnpike roads and the construction of the Rochdale Canal provided efficient transport links for the movement of raw materials and finished cloth from the mill sites to major markets and ports. Improved communications stimulated urban development in the valley bottoms.

Although the older forms of production did not disappear immediately the impact of new technology would prove to be a fundamental break with the past.

Investment

in mill building and machinery proclaimed an essential shift in emphasis

from circulating capital to fixed capital, this change permanently

altered the financial framework which had sustained the pre-factory

trade. This was not just an issue of the introduction of more machines,

it involved a complete reorientation of the principles of an essentially

rural trade dominated by the production of many independent clothiers

into an urban society commanded by factory production.

Investment

in mill building and machinery proclaimed an essential shift in emphasis

from circulating capital to fixed capital, this change permanently

altered the financial framework which had sustained the pre-factory

trade. This was not just an issue of the introduction of more machines,

it involved a complete reorientation of the principles of an essentially

rural trade dominated by the production of many independent clothiers

into an urban society commanded by factory production.

Clothiers became increasingly incapable of controlling the trade as their batch methods could not compete against mass production of the factory system. At best some clothiers continued to make an uncertain living as sub-contractors to factory owners, others had little option but to give up their textile business and join the ranks of the handloom weavers.